(May 25, 2008) “ARABIC TV does not do our country justice,” President Bush complained in early 2006, calling it a purveyor of “propaganda” that “just isn’t right, it isn’t fair, and it doesn’t give people the impression of what we’re about.”

The president’s statement, along with the decision by the New York Stock Exchange to ban Al Jazeera’s reporters in 2003, is a prime example of how the Arab news media have been demonized since the 9/11 attacks. As a result, America has failed to make use of what is potentially one of its most powerful weapons in the war of ideas against terrorism.

For proof, in the last year we surveyed 601 journalists in 13 Arab countries in North Africa, the Levant and the Arabian Peninsula. The results, to be published in The International Journal of Press/Politics in July, shatter many of the myths upon which American public diplomacy strategy has been based.

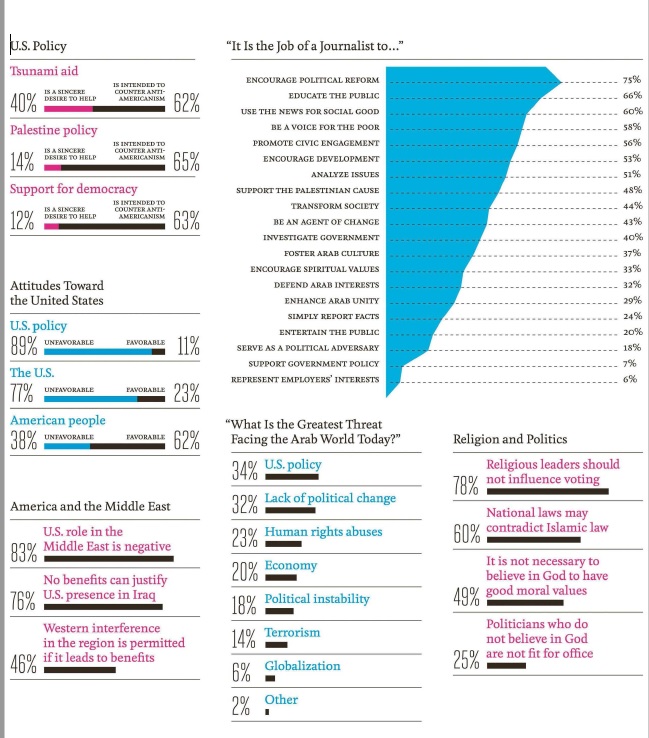

Rather than being the enemy, most Arab journalists are potential allies whose agenda broadly tracks the stated goals of United States Middle East policy and who can be a valuable conduit for explaining American policy to their audiences. Many see themselves as agents of political and social change who believe it is their mission to reform the antidemocratic regimes they live under. When asked to name the top 10 missions of Arab journalism, they cited political reform, human rights, poverty and education as the most important issues facing the region, trumping Palestinian statehood and the war in Iraq. Overwhelmingly, they wanted the clergy to stay out of politics. And, aside from the ever-present issue of Israel, they ranked “lack of political change” alongside American policy as the greatest threats to the Arab world.

Though many Arab journalists dislike the United States government, more than 60 percent say they have a favorable view of the American people. They just don’t believe the United States is sincere when it calls for Arab democratic reform or a Palestinian state, as President Bush did again this month in Egypt.

Make no mistake, the Arab press has many flaws, including being subject to state control; only 26 percent of our respondents said they felt their fellow Arab journalists “act professionally” and only 11 percent said they were truly independent in their work. Nevertheless, Arab news outlets are more powerful and free today than at any time in history. If the next administration is going to try to reach out to the Arab people, it won’t get far by blaming the messenger.

Lawrence Pintak is the director of the Kamal Adham Center for Journalism Training and Research at the American University in Cairo and the author of “Reflections in a Bloodshot Lens: America, Islam and the War of Ideas.” Jeremy Ginges is an assistant professor of psychology at the New School for Social Research. Nicholas Felton is a graphic designer in Brooklyn.